Preface

A few weeks ago I encountered a situation where, throughout the code base we had repeated logic catching an exception on a database connection object and then rolling it back in the event of an error. This wasn’t a useless repetition, it did have a point, but I felt that we could tidy clean things up by creating an auto-rollback decorator. I should note that the following examples are simplified and utilize a stubbed connection object.

Design Overview

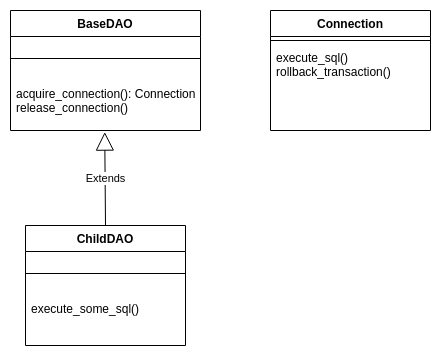

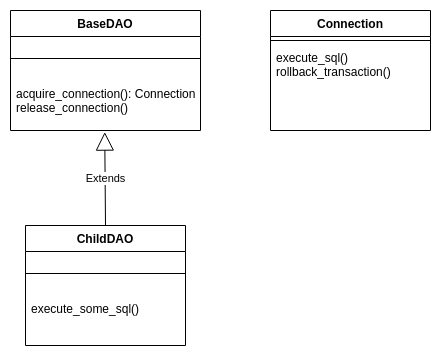

Below I have provided a diagram to help set the stage. Under the hood and “in the real world” the BaseDAO is working with a database service which houses a connection pool and dolls out connections–but that is irrelevant to the task at hand. I must stress that all the examples in this post are simplified stubs of the real world situation. Here is UML:

This means that our ChildDAO would have a method execute_some_sql() that can acquire a connection object, and that the

connection object returned has the ability to both execute sql & rollback the transaction. Here is what that code might

look like on the child class:

def execute_some_sql(self):

connection = self.acquire_connection()

try:

connection.execute_sql("INSERT INTO fake_table VALUES(dummy, value)")

except Exception as e:

connection.rollback_transaction()

My goal was to wind up with something more like this:

@rollback_on_error

def execute_some_sql(self):

connection = self.acquire_connection()

connection.execute_sql("INSERT INTO fake_table VALUES(dummy, value)")

In the above scenario the (soon to be created) decorator would catch the exception, identify the connection object & invoke the function to rollback the transaction. This decorator would enable us to remove the repeated try/except blocks around the connection executing sql and rolling back on error.

Original Game Plan

I expect the most challenging of this goal would be to identify the connection object from the decorator. The connection object should be a locally scoped variable within the decorated function. The decorator is simply another function which gets the decorated function passed to it as an argument when called. There is a really great primer on python decorators here if you need some background on how decorators work in Python.

While doing some reading on user defined functions I saw

that not only are functions objects in python, but that they should have an accessible __dict__ attribute which should

contain “The namespace supporting arbitrary function attributes.”

My initial plan was to take advantage of a built-in python function called

dir(). This built-in function will return a list of valid

attributes of the object it is called upon by sourcing the functions __dict__ attribute; My thinking was that I could

“tag” a connection object (via setattr) with an attribute in the acquire_connection method on the BaseDAO and then

use the dir command to get a list of attributes belonging to the wrapped function. I would then iterate through the

list searching for a member which contained the attribute (via hasattr). Once found I would know which variable was

the connection object, I could then invoke the rollback_transaction on the connection.

Testing The Plan…

First things first, if I am going to try and access a variable in a decorated function, I need to first create the

decorator. Here is a simple decorator, I don’t even invoke the wrapped function. All that I am attempting to do in this

test is to see if I can use the dir() command to identify the connection attribute on the wrapped function. Here is a

snippet of the experiment. The BaseDAO & Connection object are referenced, but not included in this snippet.

def test_decorator(func):

# the decorated function is an argument func

def wrapper(func):

# Here I assign the output of the dir command to a variable that I'll print.

wrapped_function_dir_output = dir(func)

# print the list

print(wrapped_function_dir_output)

return wrapper

class ExampleDAO(BaseDAO):

@test_decorator

def execute_some_sql(self):

connection = self.acquire_connection()

try:

connection.execute_sql("INSERT INTO fake_table VALUES(dummy, value)")

except Exception as e:

connection.rollback_transaction()

test = ExampleDAO()

test.execute_some_sql()

Running this test, the output is:

['__class__', '__delattr__', '__dict__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__ge__',

'__getattribute__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__', '__le__', '__lt__',

'__module__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__setattr__',

'__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__', '__weakref__', 'acquire_connection', 'execute_some_sql']

Unfortunately, the output here does not include the variable connection. I actually have no idea why it is outputting

function names belonging to ExampleDAO and it’s parent BaseDAO. I set up another test in case I messed up the decorator.

In my new test, I pass in the “wrapped” execute_some_sql function to another function peak_inside. I am skipping the

decorator, but simulating it by passing in our target function as an argument to another function which then executes the

dir() command to attempt to view the functions attributes.

class ExampleDAO(BaseDAO):

def peak_inside(self, func):

print(dir(func))

def attempt_to_view_function_properties(self):

# call peak_inside & pass our test function as an argument,

# simulating a decorator wrapping the function

self.peak_inside(self.execute_some_sql)

def execute_some_sql(self):

connection = self.acquire_connection()

try:

connection.execute_sql("INSERT INTO fake_table VALUES(dummy, value)")

except Exception as e:

connection.rollback_transaction()

test_instance = ExampleDAO()

test_instance.attempt_to_view_function_properties()

which outputs the following:

['__call__', '__class__', '__delattr__', '__dir__', '__doc__', '__eq__', '__format__', '__func__',

'__ge__', '__get__', '__getattribute__', '__gt__', '__hash__', '__init__', '__init_subclass__',

'__le__', '__lt__', '__ne__', '__new__', '__reduce__', '__reduce_ex__', '__repr__', '__self__',

'__setattr__', '__sizeof__', '__str__', '__subclasshook__']

Unfortunately this test failed as well, I still do not see any local variables of the passed in function. At least this time I do not see the instance methods from before which I couldn’t explain.

The more that I read, the less confident I am in this strategy even being possible. I need to brush up on variables and scope as well as the python data model before continuing down this particular path.

My original plan was a failure, hopefully after some more reading I can write a follow-up blog post filling in my gaps in knowledge that I’ve uncovered today. Back to the drawing board for me, it’s time for a new plan.

The Hack

I certainly had more research to do, but I also didn’t want to walk away empty-handed. I spent some time thinking about how to pull this off–how can my decorator gain access to the connection object in the function it’s wrapping? I decided that a fair strategy would be to stash the connection object in a known location.

With this new plan, I would create a dictionary on the parent class which would serve as a key/value store for the

connection–I would use the name of the function as a key. I should be able to access the function name from the

decorator by utilizing the __name__ dunder method. With this design if my decorator catches an exception, it knows

that it can look for the connection object in the connection_map dictionary by using the name of the wrapped function

as a key.

I coded my changes, and it looks like my test was a success! First up is the BaseDAO which had the most changes.

import sys

class BaseDAO:

def __init__(self):

# create an instance variable to map a function name to a connection object

self.connection_map = {}

def acquire_connection(self):

# Use the sys package to peak backwards in the call stack & fetch the caller name.

caller_function_name = sys._getframe().f_back.f_code.co_name

# simulate "fetching" connection from our non-existent db service.

connection = DummyConnection()

# add entry into dict.

self.connection_map[caller_function_name] = connection

return connection

def rollback_on_error(func):

def wrapper(*args, **kwargs):

# Surround wrapped function in try/except to identify error scenario.

try:

func(*args, **kwargs)

except Exception:

# self is always first argument, we fetch this to access the dict

self = args[0]

wrapped_function_name = func.__name__

# fetch the connection object

connection_obj = self.connection_map[wrapped_function_name]

# rollback the transaction

connection_obj.rollback_transaction()

return wrapper

You can see that we are sticking to the plan outlined in the UML. The base class now has a dictionary which will serve

to map a string to a connection object. In the acquire_connection method, we peak backwards in the call stack to

identify the caller functions name which we then use as a key to stashing the connection object on the connection_map

instance variable. You can see this get put to immediate use in the rollback_on_error decorator, which uses the wrapped

functions name to lookup the connection object in the map.

Here is the stub of our connection object (so that the test output makes sense when you see it)

class DummyConnection:

def rollback_transaction(self):

print("transaction rolled back")

def execute_sql(self, sql_to_execute):

print("I'm executing sql: ", sql_to_execute)

and of course, here is our implementation. As described in the UML, the ExampleDAO extends the BaseDAO.

class ExampleDAO(BaseDAO):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

@BaseDAO.rollback_on_error

def execute_some_sql(self):

print("I'm going to pretend to execute sql, but really throw an exception")

connection = self.acquire_connection()

raise Exception("whoops")

test_instance = ExampleDAO()

test_instance.execute_some_sql()

You can see that in this test I’m deliberately raising an exception. This way we can see if our decorator fetches the

connection object and invokes the rollback_transaction method. Here is the output:

I'm going to pretend to execute sql, but really throw an exception

transaction rolled back

Finally, some success! The behavior is working as expected. The rollback decorator is catching the exception raised from

the decorated function, it then uses the functions name to lookup the connection object in the connection_map

dictionary which it then uses to invoke the rollback function.

This hack does come with some limitations–particularly that it can really only handle one connection per decorated method; So, if for some reason you fetched multiple connections from your connection pool and only one failed it would have no way of identifying the correct connection. Beyond that, as written the duplicate key would result in the mapping being overwritten with each acquired connection.

For simple use cases, this hack is “good enough”. I will continue my reading and try to come up with a more elegant and pythonic solution, which I will then turn into a follow-up post.